One day in November of 2017, Brian Muraresku, a Catholic lawyer and financier, was researching a book that would go on to be an unlikely bestseller. What inspired the great visions of the prophets and pattern-setters of the world’s great religions? Were the oracles and saints of antiquity mentally disturbed, or just hallucinating on psychedelics? Was Moses smoking a spliff (or licking a toad’s arse) before he saw that Burning Bush? What about Belshazzar? And Jacob? Could he have been sipping a little too much mandrake wine when that mystical ladder dropped from the sky? These are not questions you would expect your average cozy mystery fan (or any other normal person) to be asking themselves, but somehow Muraresku’s book, The Immortality Key, went on to sell over 80,000 copies, landing on the New York Times Best Seller list alongside Becoming and The Meaning of Mariah Carey. No small feat.

But, long before that, Muraresku had to find some facts to support his narrative. He is an attorney, not a scholar of ancient history, and the clues were scattered amongst a maze of footnotes in obscure books and academic papers that very few people actually read. Becoming oriented in the literature would require assistance. There were only a few people in the world considered experts on such a niche topic, and one of them was named Chris Bennett. A prolific writer and researcher, he had never heard of Muraresku before that day, though Muraresku was a fan of Bennett’s, impressed by the depth and persuasion of his scholarship.

“I love Cannabis and the Soma Solution,” Muraresku told him. “I'm a huge [Gordon] Wasson fan, which is how I was first introduced to your work.”

Looking for help finding evidence for psychedelic concoctions in the Renaissance and Middle Ages, Muraresku introduced himself as the Executive Director of a non-profit called Doctors for Cannabis Regulation. It just so happened that Bennett was working on a new book and a wellspring of fresh sources. Excited to kibitz with someone else interested in the material, he happily obliged, sending Muraresku dozens of articles and leads along with several documentaries he made on the subject: Cannabis in Ancient Greece: Smoke of the Oracles?; Mithra, Marijuana, and the Myths of the Messiah; and Cannabis Roots: The Hidden History of Marijuana. Muraresku even sent Bennett’s girlfriend $60 via Paypal for a signed copy of Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, a rarity in his catalog.

“Can't wait to dive further into your opus,” Muraresku told Bennett, referencing the authors then soon-to-be-released tome Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs, and the Occult.

Besides their obsession with literature and narcotics, the two men have little in common. Muraresku is known for name-dropping and bragging about his connections to celebrities and elite society. He lives in a wealthy, historic enclave of Washington D.C. and runs in the same circles as John Podesta and Silicon Valley bigwigs like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. A psychedelic-themed art installation at Burning Man was dedicated to him in 2023, and the second edition of The Immortality Key featured a preface by Michael Pollan, the famous science journalist who helped popularize farmer’s markets and simple eating. The connections between his various enterprises is somewhat of a mystery, but some see The Immortality Key as more marketing than scholarship, embraced by billionaires like Christian Angermayer and other pharmaceutical tycoons interested in developing psychedelic drugs as treatments for depression and mental illness.

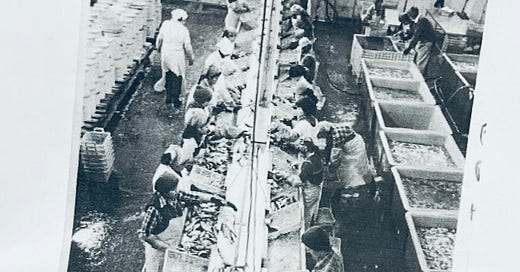

Bennett, on the other hand, is a bong-ripping blue collar surfer and self-taught scholar who labored in the rugged logging and fishing villages of rural Canada. “You know I'm a high school dropout?” Bennett once asked Muraresku. “I actually got into this stuff because of a powerful religious experience I had in 1990 reading [The Book of] Revelation and smoking a joint late one night.” That’s right, Bennett’s epiphany didn’t come to him while meditating in the pristine libraries of a Princeton or Harvard University, but while working as night watchman at a seafood processing plant in rural British Columbia. In addition to being a writer, filmmaker, and talented illustrator, Bennett is also an entrepreneur. He owned and operated a head shop called the Urban Shaman in Vancouver for close to twenty years, selling peyote, ayahuasca, and kratom along with occult books and psychedelic artwork.

Critics of Bennett’s work have accused him of being part of an industry-backed “influence campaign” targeted at Jews and Christians. Their “ultimate goal,” the critics claim, is “the elimination of religious objections to the recreational use of cannabis.” Bennett readily admits to being a “pot activist” but views his work in slightly more grandiose terms. As he later told me: “The role of psychedelic substances in the formation period of religion, when fully understood, is as much a threat to fundamental religious beliefs as Darwin's theory of evolution was to the myths of Adam and Eve in Genesis.”

Over the span of several years, this odd couple chummily bantered back and forth like two old coin collectors, discussing arcane details of archaeological digs, recipes for ancient wines, and nerding out over figures likely unfamiliar to anyone outside of the small research community surrounding psychedelics and shamanism. “You ever read the stuff about [Mircea] Eliade getting high?” Muraresku gleefully asked Bennett.”A fellow Romanian.” Muraresku was elated when Bennett passed along a lead on the discovery of a cannabis-infused wine in France. “Jesus Christ, Chris. Excellent find!” He requested Bennett collect all of the information he had on infused wines and send it in “one comprehensive email.” Months went by with the two discussing the finer points of antique intoxicants and how these substances might have influenced the development of ur-religion.

The first sign of trouble appeared soon after The Immortality Key was released, when Bennett realized he was not going to receive any credit. Furthermore, it was full of what Bennett thought were mistakes and major oversights. Muraresku, he came to believe, was spreading misinformation on a scale that might “discredit real emerging research.” Initially responding politely to Bennett’s concerns, Muraresku told him that the book was not an encyclopedia and promised to acknowledge him in future reprints. It was already sold out on Amazon, he said, and subsequent editions would “fully cite” Bennett accordingly.

“I vow to be more encyclopedic and comprehensive going forward. Which is why I need your advice.” To add insult to injury, when Bennett asked him for a small favor—a short blurb for his latest book—Muraresku declined, saying he “didn’t have time for much reading unfortunately.”

Bennett wrote a marathon review outlining his objections and sent it to Graham Hancock, the journalist turned conspiracy theorist who wrote the foreword to The Immortality Key. Hancock kindly suggested he host the article on his own website and invite Muraresku to respond. Muraresku agreed. But, as months went by, Bennett and Hancock both became irritated.

While Muraresku was making the media rounds giving “softball” interviews, he made excuse after excuse for the delay. After two months, Muraresku finally bowed out, he was “exhausted from overwork” and “unable to respond.” Hancock posted the review with a note saying that Muraresku had ultimately declined to participate. Privately, he was “surprised and disappointed.” Bennett wasn’t happy either. If Muraresku was exhausted, Bennett said, it was hard to tell. He had somehow found the energy for promotional events in which he was presented as a “visionary author” conducting “groundbreaking” research.1

To Bennett, it was obvious that Muraresku had “bit off more than he could chew,” unwilling or unable to defend The Immortality Key on its merits. Unpleasant as it may be, Bennett felt that he and Hancock both had a responsibility to “clean house.”

Hancock expressed disappointment with Muraresku as well. “I agree with you that Brian's excuse for not participating is unpersuasive,” Hancock told Bennett. “I do feel personally very let down by him, as I went the extra mile (actually many extra miles) to help him draw attention to his book, and the least I expected was minimal reciprocity in writing the article I asked him to write in response to your reviews. I feel used, frankly, but I'm not going to say that publicly.”

But Hancock was ultimately more concerned that airing their dirty laundry might provide ammunition to their enemies in academia. To Hancock, the alternative research community wasn’t just a few old fuddy-duddy’s puffing away in their personal libraries like the mythographers of yore, it was “a liberation movement fighting a significant intellectual battle against powerful and overwhelmingly dominant forces.” They should thus try finding as many points of agreement as possible and “wait until after the paradigm shifts before we start fighting publicly amongst ourselves.” Until then, he said, “it's better to present a united front and keep our internal disagreements as friendly and constructive as possible, since the damage we inflict on each other will only be used against us by the people who run the world.”

Hancock was also increasingly bothered by Bennett’s tone, chiding him for his “self-righteous anger” and “sour flavor of personal bitterness.” “Why do you so often attack people who are working in broadly the same field as you,” he asked Bennett, “and who are definitely on the alternative rather than mainstream side of the argument? This sort of internal infighting is what destroys many liberation movements.”

This was nothing more, Hancock said, than “a resentment crusade dressed up as some kind of intellectual-purity crusade.” He also accused Bennett of secretly lodging an official complaint against him on Facebook, one he says led to a formal strike. The temperature and rhetoric was ratcheting up on both sides, with Hancock charging Bennett with “whipping up a witch-hunt” against those he accused of “various intellectual crimes accompanied by a constant trumpeting of your own virtue compared with their wickedness and failings.” Bennett, he said, simply resented Muraresku’s “elevated popularity.”

Bennett denied all of this. Hancock’s support of “balderdash” like The Immortality Key, he said, was “making a mockery of the field.” Muraresku failed to cite his sources properly, Bennett said, and was also taking credit for others’ work. “Not only have authors not been credited properly, but their work has been misrepresented as well,” an apparent reference to Carl Ruck. Hancock himself was part of the problem, using his notoriety to promote dubious, sensationalized work in order to line his own pockets.

Hancock tried in vain one last time to play the negotiator. Quibbling over sources or matters of plant-identification were one thing, vicious personal insults were another. “Let's not exhaust each other with more stupid infighting. Better we agree to differ, preferably while sharing a joint, and continue to cooperate. I look forward to your new book, which I'm sure will be excellent. I will promote it in every way I usefully can when it is published.”

Bennett was unmoved and accused Hancock of promoting a “schlockfest of quackery,” challenging him and Muraresku to a public debate. Later, after Bennett left a comment on one of Hancock’s Facebook posts criticizing him for “demonizing” his critics in the mainstream archaeological community (such as Flint Dibble) instead of respectfully debating them, Hancock removed Bennett’s review of The Immortality Key from his website. On this sour note, their long correspondence ended, and Bennett became a heretic in a field he helped pioneer.

If Bennett is less well-known than Terence McKenna or Jonathon Ott, it is not for lack of productivity. Green Gold, his first book (published in 1995), featured a foreword from the legendary Jack Herer, though he lost the rights in a dispute with his co-author. (As of publication, you can obtain a copy of Green Gold on Amazon for $80.) His early attempts are now collectors items, prized by psychonauts and drug aficionados eager to learn about ancient stonerdom. Mostly sold online or at certain marijuana dispensaries, Bennett’s work is now published by the Oregon-based Trineday and his articles appear semi-regularly in Cannabis Culture. I reached out to Bennett in December of 2024 to talk about the field of psychedelic research and his dealings with both Graham Hancock and Brian Muraresku. Now 62, he lives in Nova Scotia.

VTV: Can you tell me about your job as night watchman at the seafood processing plant where you had your first religious experience?

Bennett: It was in Ucluelet, which is a small fishing and logging town on the west coast of Vancouver Island. A variety of things happened that preceded the religious experience. In Canada there had been a controversy in the 1980’s about this orphanage, the Mount Cashel orphanage. The kids that grew up there started talking about how they were molested. And I was like, ‘This is weird. Why would priests do that?’ I wasn't ever really religious but I thought, ‘I’m going to get the Bible and read it.’ At the same time, they started logging the last coastal low-growth rainforest on Vancouver Island’s Clayoquot Sound. All these environmentalists showed up and started protesting, but the whole town was pro-logging. I also started finding out about hemp. There was a documentary on industrial hemp, and I started to become interested in it. All books and magazines on marijuana were banned in Canada at that time. You'd get a $150,000 fine for selling High Times. Coinciding with all of this was the Gulf War. I had read this book on Saddam Hussein. He said that Babylon was in Iraq and was comparing himself to Nebuchadnezzar, the last king of Babylon, because he overthrew the Jews, and fired a scud missile into Israel.

So one night I was smoking herb in the fish plant about three or four in the morning reading the newspaper. And there was an advertisement for [the American televangelist] Pat Robertson, something about Revelation 18: The Fall of Babylon. Robertson’s got the pulpit behind him, he's got the tanks and jets. I was like ‘Wow, he's tying in Iraq with the Book of Revelation because Babylon's there.’ I always had a weird interest in the apocalypse, maybe because I saw The Omen when I was a kid. It was getting close to the end of the millennia and that was on a lot of people's minds too. There were Jehovah's Witnesses working at the fishplant and I'd ask them about it, ‘You think this is the end of the world?’

So when I read this thing in the newspaper by Pat Robertson, I thought, ‘I'm going to get the Bible out right now and read the Book of Revelation.’ And in the beginning John takes a scroll and he puts it in his mouth. It tastes as sweet as honey. It turns bitter in his stomach and he starts to prophesize, and I'm thinking, ‘What the hell did he eat?’ And then it's talking about these saints wearing sackcloth and giving much incense to offer, and the smoke of the incense contains the prayers of the saints. I was like, ‘Wow, this is trippy!’

I got to the end of the Book of Revelation, and I read the last verse there: ‘On either side of the river stood the tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit and yielding its fruit each month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.’ When I read that, I just felt like something just poured right into me. And I was like, ‘This is cannabis, man. All its industrial uses. This must be what the Rastas are talking about.’ I'd known of Bob Marley and those guys, but I didn't really pay too much attention.

I called my wife up at the time and she thought I was having a mental breakdown. She started bawling. And the next day I got up and said, ‘Was I tripping or did that really happen?’ And I looked out at the clear cut mountains and I thought, ‘Well, this hemp stuff is real and I'm going to start promoting that for sure. And if there's anything to marijuana being a tree of life or anything like that, somebody somewhere else will know about this.’ I started collecting whatever I could on cannabis and religion and filing it.

The first guy to import hemp cloth for making shirts was this Chinese businessman in Vancouver. I went to visit him and, on the wall he had a picture of this hippie with his head poking out between some pot plants and it said, “Church of the Universe, Tree of Life Sacrament.” I was like, ‘Holy shit!’ I called them up and we became pretty tight. They'd been around since 1969. And they sent me a book by Brother Jeff Brown from the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church. I'm not sure if you've heard of them, but they were quite big. They were making bank smuggling cannabis from Jamaica into Florida and buying mansions and putting out newspapers and doing all sorts of stuff. They got majorly busted. But this one guy, Jeff Brown, when he was in jail, he wrote a little booklet called Marijuana in the Bible. And that just made me feel like I was really onto something. So I formed a group, Patriotic Canadians for Hemp, and I started touting the wonders of the hemp plant.

VTV: Why should anyone care if Jesus or Moses were potheads or psychonauts or if the Book of Revelation is an account of someone who was taking hallucinogens? Would it say something profound about humanity or history?

Bennett: When you really understand it, the role of psychoactives in the origins of religion, it’s as much a threat to fundamentalist religion as Darwin's theory of evolution was to Genesis and Adam and Eve in that it shows the anthropological, shamanic, plant-based origins of religion. And so that's a formidable thing. You throw cannabis into the tent with Moses—and I don't think Moses existed, these are stories that are passed down, but they may identify rituals—and he's speaking to the Lord through the pillar of smoke over the altar of incense pondering a question, ‘What do I do?’ And then an answer comes back from the smoke, ‘This is what you shall tell the people.’ That's shamanism and plant-based shamanism.

And that's something the Abrahamic traditions have tried to squash whenever they've come into contact with it. Whether it be the beginning of the Dark Ages when all the gnostic and pagans were suppressed; or burning witches; or coming to the new world and persecuting people here for peyote and mushrooms and other substances that they used ritually, and defining that as sorcery and witchcraft by their standard, by the Roman Christian standard. If you take a look at the Gnostic texts—all these various sects thought that they were the “true” Christians—it’s pretty clear that those groups were using psychoactive substances.

VTV: So you see it as a kind of debunking thing? You said that it's a threat to fundamentalism…

Bennett: If Jesus’s miracles can be explained by a plant, then that's a medical application. I'm not an atheist, but I don't believe in things like virgin births or the resurrection. My own beliefs are wound up in things like collective consciousness, instinctual function, instinctual memory, genetic memory, that sort of thing. I think that the Bible is dangerous. It's bringing us to an apocalypse. I don't think it's a good thing.

VTV: You just hit on something really interesting. Which is, these ideas can be used either way. They can be used to dismiss religion, but also, if miracles can be explained naturally, you could use that to support the Bible and say that it's all true.

Bennett: I've had many people running with my stuff who were total believers.

VTV: You said to Graham Hancock once, when you were arguing with him, that “Ninety percent of this research is bologna.” Why did you say that? What did you mean?

Bennett: I was talking about books like John Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross and Jerry Brown's The Psychedelic Gospels.

VTV: Can you briefly explain who Allegro is and also why his work is bologna?

Bennett: Well, Allegro, he was an actual biblical philologist and linguist and worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls. His book, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, has the wackiest etymology. No other linguist or etymologist shares his breakdown of words. He even says the term cannabis originally meant mushroom. And he ties it in with a Sumerian language and makes a case for it. But there's lots known about the etymology of cannabis, it's from an Indo-European root. He's far away from all the standard research when he says things like that. And his breakdown of Jesus being a mushroom and all the different names of the people in the Bible somehow always relating back to mushrooms, it’s just bunk. Nobody accepts it.

Brown's book is more based on medieval paintings of Jesus where people are interpreting stylized trees as mushrooms. Some do look a bit like mushrooms. But a lot of these European medieval artists, they never went to the holy land. They never saw palm trees. So they were drawing from written descriptions and what little they knew of it. And a lot of the art itself is pretty primitive and childlike. And so there's these mushroom-like trees, and all of a sudden, they become psychedelic mushrooms and indications of mushrooms as a sacrament. And somehow they tie these traditions back to the Bible itself with no written evidence from the time period that indicates people were using mushrooms, no archeological evidence, and nothing to fill the gap between the biblical era and the medieval time period when a lot of these paintings were put together.

Likewise with people like Mike Crowley [the author of Secret Drugs of Buddhism]. His claims of mushrooms and Buddhism are largely based on images of parasols that have a whole other symbolic identity in Indian and Buddhist art. But somehow to him, they're mushrooms. And mushroom use was this secret thing that they had to convey in art, and nobody figured it out until he came along and deciphered it. It's nonsense.

I had no background in researching or writing when I started. Some of the things I wrote in my earlier books, I probably wouldn't repeat. And it's always been a part of the process for me, trying to sort out my biases from facts, and trying to be honest with myself. And I think that's a problem for a lot of the researchers in this field. One thing I like about researching cannabis, as opposed to mushrooms, is there's so much actual archeology. You can also trace the word cannabis back in different languages. And so there's actual references in the Vedas and other ancient documents. Whereas so much of the research about mushrooms and ergot is all based on speculation. And you're left with their interpretation. When it comes to things like something that looks like a mushroom in a painting, it's kind of iffy if you ask me.

VTV: Would you like to speculate on Allegro’s motivations? Because, unlike some others, you can't make the argument that Allegro was trying to make an excuse for his own drug preferences. I don't think he ever used a psychedelic.

Bennett: Well, for one thing, the Soma book by [Gordon] Wasson was hugely popular then and had created a lot of interest. It was the same time period and it preceded anything Allegro had written on mushrooms. And so it created a bit of a buzz around these things.

VTV: So you think he was just trying to capitalize on Wasson’s work and get attention?

Bennett: He may well have believed his own bullshit. That's the problem I'm talking about with a lot of this work. And one that I try to avoid and why I listen to my critics. When I get something critical written about my work, I respond to it. Because I don't want to bullshit anybody, not even myself. A lot of these guys, they just ignore it. Even guys like [Carl] Ruck, who I have a lot of respect for, so much of his work is based on Wasson's mushroom theory which is easy to take apart. You don't find a lot of Vedic scholars supporting it. And if you go into India with Indian scholars that have studied the Vedas, there's a whole bunch of them that say it's cannabis. I can't find any that say it's the mushroom. That’s more of a western idea. But it's become pervasive and you can't even discuss it. It's in encyclopedias. It's just become widely accepted without any real analysis of the texts.

VTV: Do you think that Carl Ruck has made a contribution to the humanities?

Bennett: I think he's created a situation where the study of psychedelics playing a role in the formation of the world's religions and myths can be taken seriously. The term entheogen itself is a major contribution to the way we look at these things. He's taken it from fringe to something that can be taught at a university and taken quite seriously, somebody can write a PhD paper on it. I had a close relationship with Ruck. He reviewed my book, Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, in the London Sunday Times. And I brought him out for a couple of conferences. But when I wrote my book on Soma, I started to pick apart Wasson’s work and I think it was not seen favorably by Ruck. Because so much of what he's written is based on the foundation that Wasson built, and once you take that away, the whole thing just starts to fall down. I have a lot of respect for Carl but there's a lot of his work that I don't think stands up to scrutiny.

VTV: How did you first come into contact with Brian Muraresku?

Bennett: He sought me out. He had read my book Cannabis and the Soma Solution and several other books with themes similar to his. He contacted me asking lots of questions, saying what great scholarship it was. And I kind of forgot about it. I get a lot of young researchers writing to me and I’m happy to help. Then his book came out and everybody's going, ‘Have you seen this book?’ Everybody was asking me about it. So I looked it up and I thought, ‘Oh, I'll see if this guy's on Facebook.’ And I saw we were friends. And then I realized we had corresponded a couple years back. I didn't even realize it was this dude. And so I was kind of stoked at first, but I also felt that there were overlaps of research that were discussed quite thoroughly in those books, all three of my books that he read. Things like infused wines and connections between Jesus and Dionysus and Soma. So I felt that he should have cited me in reference to some of these themes and where these ideas originated.

He tells this story about a verse in the Bible and he describes this whole situation with a priest in a library and it was pretty much a repeat of how it connected the Eucharist with Soma. That was right in my book. It made me wonder if the whole story was fake. I think that a lot of people's ideas kind of made their way in there. I go out of my way to reference people and cite their work and give people credit. And also to show that these aren't ideas that I came up with. I'm building on the foundation of earlier researchers. I thought the way he presented it took credit for other people's research that he was influenced by. I called him out on it, and it was awkward.

VTV: What did you make of Hancock's argument when you brought this up? That the alternative research community is some kind of “liberation movement” and that you should present a “united front.”

Bennett: I think he's going to be remembered in the long run as a quack. That's going to be his legacy. A century ago there was all sorts of quackery that was really popular. It doesn't stand up to any real scrutiny. I can't say I'm having much greater success than these guys, even with what I think are more stringent presentations. It's hard to break through that academic barrier. But there are academics writing about these things too. I think Hancock presents work that's purely speculative on his website. What the psychedelic historians need is a dose of critical thinking. But when you do challenge them, it's unpopular.

VTV: Much of the psychedelic literature—Terence McKenna, Albert Hofmann, Timothy Leary—is, I would argue, part of a larger anti-Christian polemic that goes back to Nietzsche. McKenna railed against Christianity. Hofmann railed against Christianity. Leary railed against Christianity. The Immortality Key quietly reverses course. It proposes using psychedelics to reinvigorate Christianity.

Bennett: I am definitely anti-Christian, Roman Catholicism. One of the things that got me reading the Bible was that priest that molested children. That's why I picked up the Bible. Evangelicals put Trump in power. It is an institution that burned witches and scientists alike. There's lots of reasons to be against it. It's like a ball and chain to the Bronze Age. I'm not against Jesus. Jesus is okay. Marijuana in the Bible was pro-Bible. And there's been people that formed Christian churches around cannabis. That's one of the things I don’t like about his book [The Immortality Key]. I think he's just a Catholic apologist. He was raised Catholic so he tries to fit it in with that. He's definitely trying to get the church on board and sees this as a way to revitalize the religion with some new energy. I just can't see it flying. He might get some schisms off the church that break off. Even Santo Daime, it's Catholic psychedelic-type stuff, but it's never going to be accepted by the Vatican.

VTV: At some point you sent a message to Muraresku quoting Patrick McGovern [a distinguished archaeologist at UPenn who appears frequently in The Immortality Key] where he seems to be annoyed, alluding to Muraresku “sitting down with purveyors of extraterrestrial theories of ancient history and archaeology,” a reference to him appearing on the Joe Rogan podcast with Graham Hancock. You sent this to Muraresku and said, ‘Hey, I thought you guys were buds?’ Why did you do that?

Bennett: Yeah, I did. What happened was, I read his references. McGovern certainly comes off as a strong ally of Murareksu’s in The Immortality Key, so I contacted him to ask him some questions about that. He was quite clear that that was not the case. He felt that he was misrepresented. McGovern is somebody that thinks cannabis was a part of the Soma preparation and Muraresku makes no mention of that.

VTV: You also asked Muraresku if he was going to flee the country over the election of Donald Trump. Why?

Bennett: That was 2017. He said he was temporarily relocating to South America.

VTV: What did you think about that?

Bennett: Well, he's a lawyer. I just assumed he had money.

VTV: You also brought up Aleister Crowley in your correspondence. I was struck by the parallels between Crowley's ideas and some of the themes in The Immortality Key. The reenactment of the Rites of Eleusis, the interest in drugs, and this mystical-occult idea of starting a new religion or kind of re-enchanting the world. Is that right?

Bennett: Yeah, I would say that that's true, but not just Crowley. [Louis Alphonse] Cahagnet wrote a book called The Sanctuary of Spiritualism that he thought was going to be the new Christianity. It was twelve firsthand accounts of people that had eaten three grams of hash. And he thought this was going to create a whole new religion. There were other occult figures as well that thought like that. Crowley's initial experience of Samadhi was on hashish. That gets played down. It's likely that that is also the source of his Book of the Law. He was a real pioneer in the study of peyote as well.

VTV: Do you agree with Graham Hancock that there is basically an academic conspiracy to hide this research and other alternative ideas about prehistory?

Bennett: I don't know. Take a look at my interaction with Dan McClellan, for instance. He's just not quite convinced. It’s all about trying to present this work with academic rigor, and oftentimes people writing about this aren't academics, but that’s changing. It’s in the process of happening. It’s just taking more and more rigor, better presentations, listening to what critics say, what archeologists and other people have to say, and analyzing it. I used to be bothered a lot more about getting ripped off, but now I just kind of go, ‘Okay, whatever.’ I'm not counting on this for my income. I had a shop, and I invested money in real estate and other things. So I've got a comfortable life although my books didn't receive literary fame. Every time I wrote a book, I thought, ‘Oh, this one's going to change the world. This is it.’ It didn't happen.

Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible has all sorts of spelling mistakes in it. I'm not the same as somebody that's gone through years of university. I'm no dummy, but I come from a different place. I've come to my ideas differently than other people. And sometimes I think these university educationists get caught in a pigeonhole type of view and it's hard for them to see outside of it. The idea of cannabis use by the ancient Hebrews, before the discovery at Tel Arad, no actual biblical scholars were suggesting that. It was just so fringe, and now there it is. And hopefully more archaeology comes to light because that's what can't be argued with.

VTV: You mentioned your store. What was the Urban Shaman?

Bennett: The Urban Shaman was a shop I had in Vancouver. I think I started it around 2001 and it went until about 2020. I realized a lot of plants had not been scheduled by the drug laws, including many of the plants used for ayahuasca and peyote. They were not illegal in Canada. They were going to outlaw and create an exemption for the Native American church but the government here felt at the time that that might open up an avenue for other court cases involving other plants, so better just to leave it off the schedule altogether because they were hard to get in Canada. I thought, ‘I can sell these plants.’ So I started providing them and also providing things like rare books on drugs and that sort of thing and created this shop, the Urban Shaman, along with a mail order business. And that did very well. Jonathan Ott inspired me. Jonathan Ott and his partner, Rob Montgomery, had a mail order psychedelic business. And he helped me with getting suppliers and other things and what plants to carry. Rob passed away a few years back. Great guy. Those guys inspired me in a lot of ways to start that business.

VTV: Were you also inspired by Terence McKenna?

Bennett: I talked to Terence in the early 1990s. He read my first book, Green Gold, and gave it a nice plug. I talked to him on the phone. I have a couple of letters from him. He’s definitely a big inspiration. I like Food of the Gods a lot. I thought his other stuff about 2012, the elves, all that was nonsense. But Food of the Gods and some of the ideas in there introduced me to [American psychologist] Julian Jaynes. I think that is McKenna's greatest contribution to psychedelic historical research, bringing in Julian Jaynes’ The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and combining that with psychedelics.

VTV: Is there any similarity between what’s happening here culturally with the “psychedelic renaissance” and anything happening in Canada now?

Bennett: Yeah, the Vancouver scene. Like I said, I started providing psychedelics early on in Vancouver and supplied a lot of ceremonies and things like that. It got taken over by this Tony Robbins [the self-help guru] crowd and I got turned off. I basically retired a couple of years back. I was trying to get this psychedelic retreat center off the ground and then Covid hit. A lot of the people that were coming around were QAnon-types or into this “plandemic” stuff. So much of the scene was like that. And I guess I'd had higher hopes of psychedelics bringing enlightenment. Not that I don't think they're useful tools and they can contribute to that, but you can just as easily end up crazy as shit like Charles Manson. It could go either way. It really depends a lot on the individual using them and how they're introduced and lots of variables there. I'm not knocking the potential of psychedelics, but I thought they were more of a magic bullet. And that kind of disillusioned me.

I have been a utopianist my whole life looking for a better world and to change the world. And around that same time, I just lost faith in humanity. I've come to the conclusion that there’s not a government in the world that's going to take on things like climate change or what’s going on in the Middle East. Maybe some of these smaller countries like New Zealand or something. But any major world power, there's no way, and so we're just on this path of destruction.

VTV: You knew the late Gatewood Galbraith [a famous marijuana activist and political gadfly from Kentucky]. What do you remember about him?

Bennett: He came to Vancouver a couple of times. I just remember him being a really inspiring guy. Interesting, charismatic, a lot of fun to be around. He read my book Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible and gave a copy to Willie Nelson. I thought he was awesome. I was sad to hear that he passed away unexpectedly.

VTV: Do you have any advice for young people, in terms of drugs?

Bennett: Yeah. I think that humanity has a natural right to the plants of the earth. And this is more important than freedom of religion and freedom of speech. This is an inherent natural right like our right to air and water. But with that right comes responsibility, and that responsibility is yours. If you choose to explore any of these plants, you want to go into that from a place of knowledge. And you want to do a lot of research on any sort of psychedelic or hallucinogenic substance before you do it. You don't want to just take something from somebody and ingest it. You want to know what you're doing and the history of it, the effects of it, the potential dangers of it, and that's your responsibility to do that.

VTV: Beautiful. Chris, thank you so much. This has been a real pleasure.

Bennett: Hey, cheers, brother.

One podcast host even referred to Mr. Muraresku as “our era’s equivalent to Galileo.”

I'm just finishing up your conversation with Danny Jones which I paused to come find your articles. We need to talk. I feel like we can fill in some of each others gaps.

Wow. Just wow.